Aussies Claim No Brain Tumor Link; Skepticism Abounds

Why Were Older People Excluded?

No One Wants To Talk About It

The incidence of brain tumors in Australia did not increase between 2003 and 2013, according to a new analysis by the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency (ARPANSA) and the Australian Centre for Electromagnetic Bioeffects Research (ACEBR). This means that there can be no link between the use of mobile phones and brain cancer, they claim.

If such an association were true, “then the brain tumor rates would be higher than those that are observed,” states an ARPANSA press release that accompanies the new paper published in BMJ Open.

“People say mobile phones can cause cancer but our study showed this was not the case,” said ARPANSA’s Ken Karipidis, the lead author.

Others are skeptical. The work is incomplete and misleading —or worse, they say.

Karipidis and ACEBR’s Rodney Croft led the new study, which was carried out under an A$2.6 million (~US$1.8 million) grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. ACEBR is based at the University of Wollongong in New South Wales.

Only Brain Tumors Among Those Under 60 Are Included

The new survey covered more than 16,800 cases of brain tumors recorded in Australia between 1982 and 2013. Surprisingly, Karipidis and Croft excluded all cases who were 60 years of age or older at the time of diagnosis.

That decision has prompted widespread criticism. The main concern is that it leaves out the largest segment of the brain tumor population. It is well known that people are more likely to develop tumors as they grow older.

In the U.S., for instance, the median age of brain tumor cases is 60, according the American Brain Tumor Association (that is, there are more cases among those older than 59 than those who are 59 or younger). If a similar distribution applies to Australia, Karipidis and Croft would have ignored a majority of all brain tumor cases in their analysis.

Limiting cases to those 59 and younger seems “quite bizarre and unnecessary” commented Vini Khurana, an Australian brain surgeon and the director of CNS Neurosurgery in Sydney. Khurana has long followed and written about the cell phone controversy.

Others were more blunt. “It’s a biased study,” tweeted Joel Moskowitz of the University of California, Berkeley who runs the Electromagnetic Radiation Safety Web site.

According to Karipidis and Croft’s paper, the reason for ignoring those over 60 was to allow a comparison with what they call the “modest” increase in brain tumor risk seen in the 2010 Interphone study. The Interphone findings were partly responsible for IARC’s labeling RF radiation a possible human carcinogen.

When I requested clarification, Karipidis would only reiterate that he was following the lead of the Interphone study group. “As stated in the paper we restricted the data to the 20-59 age range to directly compare with the Interphone results,” he told me through an ARPANSA communications officer. He declined to be interviewed for this article.

I asked Bruce Armstrong, an emeritus professor at the University of Sydney School of Medicine for his opinion. Armstrong led Australia’s Interphone team and is now working on the Mobi-Kids project, investigating brain tumor risks among 10-24-year-olds. He acknowledged the problem with the study design.

If Karipidis’s team had behaved “rationally,” Armstrong told me, they would have done it differently. “Interphone excluded people over 60 because it was argued at the time that these people had little mobile phone use,” he wrote, adding that, an analysis of trends in post-1944 birth cohorts would have been a better approach.

As Armstrong points out, Interphone had its own reasons for excluding the older cases. Karipidis and Croft’s ecological analysis —a search for trends— is totally different from the case-control design used in Interphone. They have no information on the use of mobile phones by those with brain tumors. Interphone, on the other hand, went to great lengths to estimate each participant’s exposure to RF radiation. What applies to one study may not apply to the other.

ICNIRP’s Rodney Croft Has No Time for Questions

Given Karipidis’s reticence to engage, I turned to Croft. I sent him the same short list of questions I had sent Karipidis. These included why had they excluded those over 59 and whether they had done a separate analysis that included the older group of brain tumor cases.

But he was too busy to comment, he said, and would defer to Karipidis. When I told him that Karipidis was unwilling to answer my questions, Croft replied that he would “liaise” with him and get back to me. That was the last I heard from Croft.

Croft, a psychology professor, is a chief investigator at ACBER and the principal investigator of the multimillion-dollar government project under which the brain tumor study was carried out. He is a full member of ICNIRP and Karipidis is a member of the Commission’s Scientific Expert Group (SEG). ICNIRP has long strived to counter any suggestion of a link between brain tumors and cell phones.

Karipidis is so convinced that cell phones are safe that he tells everybody there’s no need to take precautions. “As a scientist, the evidence [of a health risk] is not good enough,” he said in a press interview. “I don’t feel the need to use the speaker or hands-free.” He went on to reassure the public that 5G technology, now being phased in worldwide, is “nothing to worry about.” (For a contrary view, see this recent paper from IT’IS in Zurich.)

Countering the Increase in GBM Seen in the U.K.

The Australian study runs counter to a paper published earlier this year by Alasdair Philips and coworkers in the U.K. They showed that the incidence of glioblastoma (GBM), the most aggressive type of brain tumor, more than doubled in England between 1995 and 2015.

Karipidis and Croft reported that they saw no increase in any of brain tumor subtypes, including GBM.

“By stopping at age 59, they are missing the group with the largest increase in GBM, and those with the most exposure to mobile phone radiation,” Philips told me from his home in Scotland. “This is impossible to justify.”

“Frankly, I find their limited analysis shocking and I don’t understand how it cleared peer review,” Philips said.

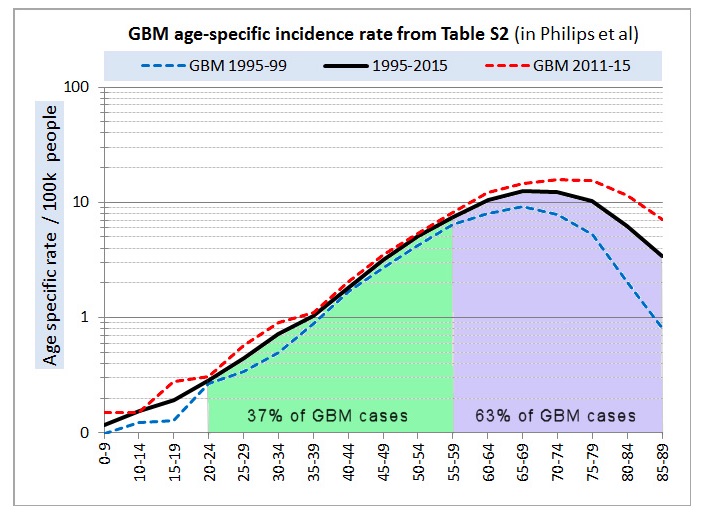

To support his argument, Philips sent me a figure based on some supplementary data released with his paper last spring:

Source: Supplementary Materials to Philips et al., 2018.

“You can see that, for GBM, ignoring those over 59, eliminates 63% of all the cases in England,” Philips said. “Essentially the entire increase in GBM over the last 20 years is among the older group of people —the difference between the red and blue dotted lines. If we had eliminated that group, we would have reached a similar conclusion as Karipidis.” [Note the incidence of GBM is plotted on a logarithmic scale above. To see the same graph on a linear scale, click here.]

“But doing that would be nonsensical.” Philips said, “The Australian paper is nothing more than misleading pseudoscience and should be withdrawn.”

January 10, 2019

BMJ Open has posted a response to the ARPANSA/ACEBR paper by Alasdair Philips.

He concludes, in part:

“In my opinion, their article unreasonably and misleadingly distorts the literature on modern detailed brain tumour incidence trends. The fact that it passed peer-review raises questions as to the competence and independence of the review process.”