How Money and Power

Dominate RF Research

The Lai-Singh DNA Breaks 30 Years On

A Conversation with Henry Lai

Unremarkable science can sometimes tell a remarkable story. Two papers that were published in the last few weeks —and passed mostly unnoticed— have important, though very different, backstories.

One offers a surprising glimpse of change in the usually static field of RF research, while the other shows how much has stayed the same over the last many years. Yet, in the end, they offer the same well-worn message, always worth repeating: Those who sign the checks, run the show.

The two papers come 30 years after Henry Lai and N.P. Singh began an experiment at the University of Washington in Seattle that would set off alarm bells across the still-young cell phone industry —and the U.S. military. Lai and Singh would show that a single, two-hour exposure to low-level microwave radiation (today, we’d say RF) could lead to breaks in the helical strands of DNA in the brains of live rats.

Physicists have long said that RF is too weak to break a chemical bond in DNA or anywhere else. Lai-Singh were not trying to rewrite the laws of physics, only reporting that they saw more DNA breaks when rats were exposed to RF radiation. They had some ideas about what might be going on but were the first to concede that they didn’t really know.

The news from Seattle spread quickly. Lai had a reputation as a careful investigator with years of experience. Singh was even better known. He had developed the comet assay, which had become a standard technique for measuring DNA damage. As for the university’s bioelectromagnetics lab, it was state-of-the-art. It had been designed and built with support from the U.S. Air Force (USAF) by Bill Guy, a talented engineer, who would become one of the cell phone industry’s most senior RF experts.

The DNA experiment came at a bad time for Motorola. Several months earlier, on January 21, 1993, David Reynard, a Florida businessman, told CNN’s Larry King that his wife, Susan, had died of a brain tumor which, he believed, had been caused by a cell phone. He was suing for damages. At the time, Larry King Live was the most widely watched show on the cable news channel. Reynard made headlines. Shares of Motorola tumbled the following day, losing four percent of their value on the New York Stock Exchange.

Lai-Singh offered the missing link: If RF could indeed break DNA, it was no stretch to believe that cell phone radiation could lead healthy brain cells down the path to cancer. “This is a possible mechanism for causing DNA damage that could have significant health effects,” a senior FDA official told me at the time. (That official, Mays Swicord, would later join Motorola as director of its RF bioeffects research program.)

The telecoms knew the Lai-Singh results spelled trouble. Six months before they appeared in print, Motorola scientists flew to Seattle to check out their lab. At the same time, Motorola PR was looking for ways to control potential fallout —they called it war-gaming Lai-Singh.

The DNA paper cleared peer review and was published in the summer of 1995. It took up just four pages in the journal Bioelectromagnetics. Lai-Singh became a rallying cry for those who maintained that the cancer threat is real. The radiation may well be too weak to break a chemical bond, they said, but RF could, by some as-yet unexplained mechanism, set off a cascade of reactions leading to the same result: broken DNA.

Threats from All Over

In the months and years that followed, Lai would be threatened —sometimes subtly, often less so— by telecom agents of one kind or another. Even Bill Guy, his former colleague, turned against him. Guy tried to stop the DNA experiments, going so far as to contact the NIH and call for Lai’s research grant to be terminated.

George Carlo, who was in charge of the wireless industry’s (CTIA) health research, wrote to the president of the University of Washington all but demanding that Lai be fired. His letter was laced with threats of litigation.

At one scientific conference, a Motorola consultant approached Lai with some “friendly” advice: Stop the DNA work or your career will be ruined. Lai didn’t stop, yet, it all worked out.

Henry Lai (photo: Seattle Magazine)

Henry Lai (photo: Seattle Magazine)

Lai retired and became a professor emeritus in 2012, but he never stopped working. Over the last decade, he has published more papers and literature reviews than many an assistant professor seeking tenure. A couple of years ago, he and two colleagues completed a three-part survey of electromagnetic effects on plants and animals. Together, the papers run over 200 journal pages, with more than 1,000 references.

The field of RF genotoxicology has mushroomed since that first DNA breaks paper. Lai still tracks the literature and, on an almost daily basis, updates his bibliographies. As of last week, he had tabulated 440 papers on RF genotoxicity: 70 percent show effects and 30 percent do not.1

[A copy of Lai’s bibliography of 440 RF genotoxicity papers2 is available here.]

I have known Henry Lai for some 30 years, and for much of that time we have been in frequent contact, often to compare notes about the latest scientific papers to hit the journals. What follows stems from our many recent exchanges, mostly about those two papers that appeared in April.

Gene Expression Takes the Stage

The importance of RF–DNA breaks to the cancer controversy has receded since the 90s. The focus has shifted to whether RF disrupts the expression of the genes coded in the DNA. That is, whether the radiation can change the way genetic information is translated into action. Changes in gene expression can be a consequence of an epigenetic effect.

Every cell in a living organism contains the same DNA. Gene expression determines what happens in any given cell: whether it turns into a fingernail or an eyelash. Anything that muddles the gene’s fabulously intricate instructions may threaten not only the viability of that cell but the health of the organism itself.

In one email, I asked Lai to put the gene expression work in the context of the earlier work on DNA breaks. Here’s what he wrote:

“Changes in gene expression can have profound downstream effects on physiological functions. They could explain most of the biological effects of EMFs that have been reported in the literature. DNA breaks, on the other hand, play only a minor role in causing these effects.”

Among the 440 papers in Lai’s genotox bibliography, 127 address gene expression. Of these, 99 (79 percent) show changes, he told me, an even higher rate than for all types of genetic effects.

On April 1, Lai sent me a copy of a study that had just been posted by Bioelectromagnetics, the same journal that had published his original DNA paper. It caught my attention. My first thought was that this paper would give the 5G lobby a bad case of heartburn. It showed epigenetic effects in human skin cells after a single, one-hour exposure to very weak 900 MHz radiation —a frequency commonly used in wireless communications.

Up to now, the skin has not been a major focus of attention, but that will likely change as 5G transmitters start using higher frequencies (millimeter waves) which are absorbed in the outer layers of skin.

There’s nothing “scientifically new” here, Lai told me when I asked for his opinion. But, he stressed, the paper shows some “serious effects” after low-level exposure. He was referring to changes in DNA methylation, an epigenetic effect for which there is a rich literature. Ten years ago, in a highly cited review, a group at UCLA described DNA methylation as “a major epigenetic factor influencing gene activities.” They went on to point out that improper methylation of a single gene can have “drastic consequences.”

The new study identified 114 genes that were “significantly differentially methylated” following a single one-hour exposure to RF radiation.

As Lai had noted, the RF exposures (SARs) were very low3: less than 0.01 W/Kg —a tiny fraction of what current standards assume to be the threshold for RF ill effects (4 W/Kg under the ICNIRP and IEEE limits). The new experiment had exposed the skin cells to an SAR sixty times lower than Lai-Singh had used (0.6 W/Kg).

But even the tiny SARs were not that unusual, according to Lai. “There are many studies which show effects below 0.01 W/Kg,” he told me in one exchange.4

A New Approach?

What is new —and surprising— is who ran the experiment: A group at a USAF base in San Antonio. The lead author is Jody Cantu of the Biological Effects Division of the USAF Research Lab at Fort Sam Houston. (Cantu is listed in the paper as an employee of the General Dynamics Corp.)

“I am surprised that they let this be published,” said Lai. “They will be demoted from top gun to bottom gun,” he quipped, quickly adding, “But I’m glad they did it.”

The U.S. Air Force has always had a dominant role in RF bioeffects research. It began in the 1950s with the Tri-Service Program, which was led by Col. George Knauf, a USAF physician. He understood the risk of opening a Pandora’s Box full of possible RF effects. Knauf urged his grantees to be “extremely cautious” when describing their RF experiments. “You must remember that this subject has enormous public appeal and lends itself readily to sensational headlines in the press,” Knauf warned them at a conference held at an Air Force base in upstate New York in 1958. Use your new data wisely, he pleaded: “Please do not betray our confidence.”

Compared to what would follow, the Knauf era was relatively open. Information had always been closely held, but it became even more restricted when the USAF began developing RF weapons. Many health studies were now classified and totally inaccessible to those without a security clearance.

On top of that, it was hard to ignore the USAF’s multiple conflicts of interest. Its mission was developing high-power radars, communication systems and weapons, not pushing back the frontiers of biology. No one believed that senior staff would ever allow anything found in the lab to interfere with getting the job done.

“A Bunch of Crap”

Here are a few examples —from the pages of Microwave News— of the ways the USAF has muddied the RF waters:

• When the USAF completed an RF animal study in the early 1980s to investigate the long-term effects of its high-power PAVE PAWS radars, to everyone’s surprise, the exposed rats had higher rates of cancer. The USAF did everything possible to suppress the findings. It took eight years for them to be published in a journal.

• In 1992, a dispute between two USAF labs over low-level RF effects broke out into the open. Cletus Kanavy, the chief of the biological effects group of the Phillips Lab at Kirtland AFB in New Mexico —site of EMP testing— wrote to his superiors that “it is absolutely ‘shocking’ to hear [the] Armstrong Lab [at Brooks AFB in San Antonio, TX] deny the existence of any biological effects that are not thermal” (see “USAF v USAF”). Armstrong prevailed and Kanavy’s dissent was snuffed out.

• In 2001, after years of secrecy, the USAF confirmed that it had developed an electromagnetic gun for crowd control. The weapon, called Active Denial, uses millimeter waves to cause burning pain. The Marine Corps Times described it as a “people zapper.” Yet, here’s Michael Murphy in a USAF press release: “We’ve done a lot of research on this technology and have shown there are no harmful health effects.” Murphy was the director of the directed energy bioeffects division at the Armstrong Lab and was helping write the current IEEE/FCC exposure limits. At the time, Ross Adey, a senior RF researcher with high-level security clearances, put the obvious into a soundbite. What Murphy said is “a bunch of crap,” he told me.

As far back as I can remember, the USAF had a reputation for “buying” research to counter results that point to ill effects. Someone was always willing to take the money and do what’s needed, whether it’s running experiments or writing literature reviews.

Against this backdrop, the publication of Cantu’s epigenetic paper may signal a significant shift. The USAF allowed her to report effects which, in earlier times, they would have sought to invalidate.

“Yes, it surprised me,” James Lin told me. Lin, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois Chicago, was the editor of Bioelectromagnetics from 2006 until last summer. Cantu’s manuscript, submitted in February 2022, was one of the last to go through peer review under his leadership. It would take more than a year for it to be accepted for publication.

To be sure, the USAF has not turned over a totally new leaf. No one I contacted there wanted to talk about the new paper —they were, perhaps, even less accessible than Col. Knauf had in mind.

Cantu declined to be interviewed. Similarly, Bennett Ibey, who works for the USAF Research Lab in San Antonio, did not respond to an email inquiry. He wouldn’t even tell me in which AF branch he works. But I can say that he is one of the six associate editors of Bioelectromagnetics and sits on the board of directors of BioEM, which publishes the journal.

A Never-Ending Obsession

The second new genotox paper appeared in the International Journal of Radiation Biology about ten days after Cantu’s. It offers a far less encouraging message. It’s the latest chapter in a thirty-year campaign to discredit Lai-Singh —and genotox effects in general.

At the center of this vendetta is a woman known by a mononym, Vijayalaxmi. Vijay, as she is called, has been associated with the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio for the last 30 years. (She is now on the adjunct faculty.) Her principal sponsor over the years has been the USAF, for which she has carried out numerous RF–genotox experiments.

She has reported an effect only once in her long career —that was in her very first RF paper back in 1997. It’s easy to miss because the effect is not in the published paper. It states that there was “no evidence for genotoxicity.” The effect showed up a year later in a correction. There, Vijayalaxmi acknowledged and apologized for the error which had hidden a statistically significant RF effect in mice blood and marrow cells. She then went on to argue that it likely had no biological relevance. (She later published a correction to her correction.)

Vijayalaxmi has been waging war against Lai-Singh for so long that I wrote about it 17 years ago!

Back then, the attacks were nastier. In March 2005, she and Sheila Johnston, a London-based industry consultant, circulated a weirdly amateurish attack, with the message “Lai’s science has failed CONCLUSIVELY.”

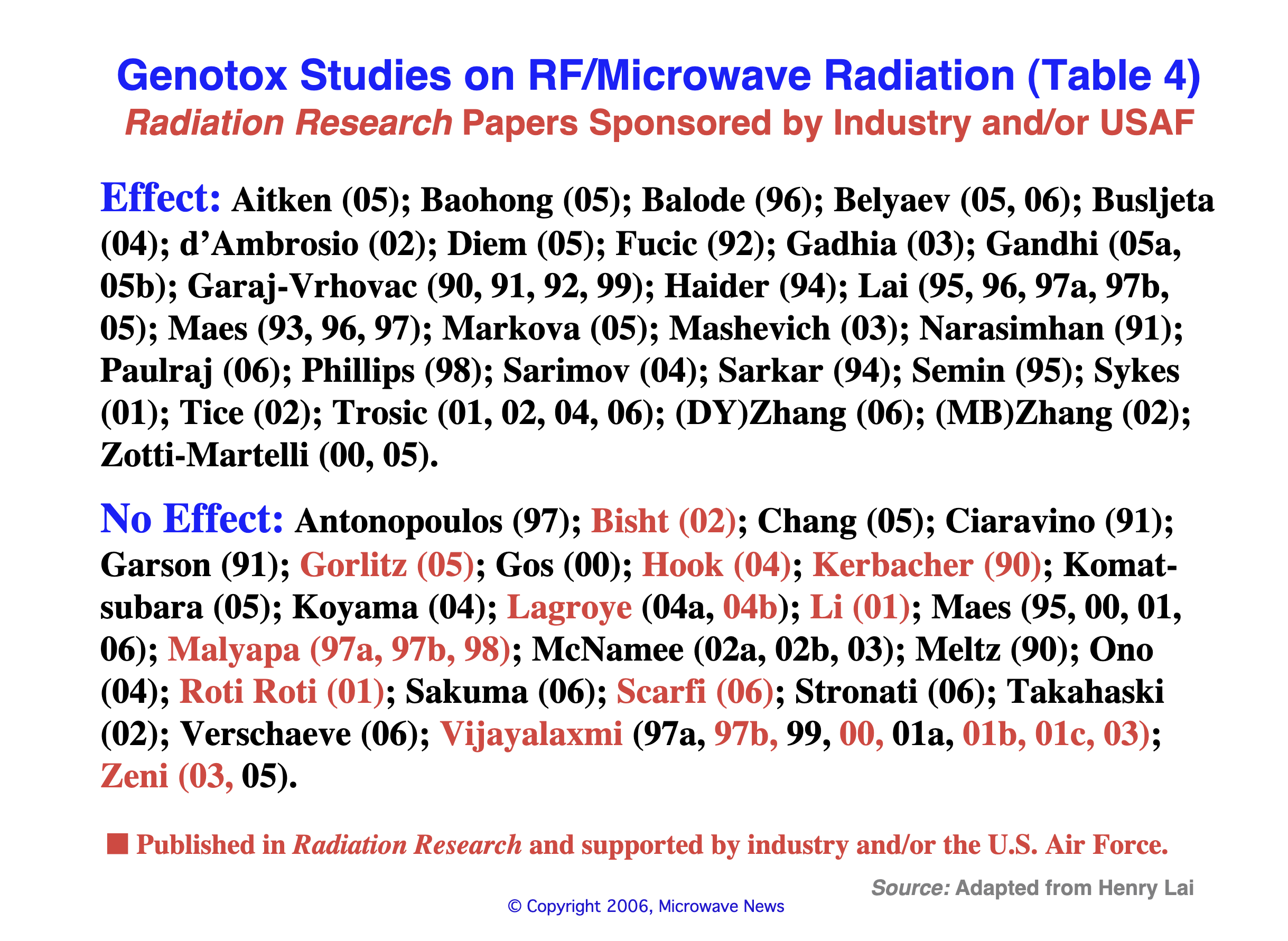

The slide below, from my 2006 article, puts eight of Vijayalaxmi’s early papers in the context of others on RF genotoxicology. Her five in red, published in Radiation Research, were funded by the USAF. Her other three were also sponsored by the USAF, but are in the International Journal of Radiation Biology.

Source: Microwave News, July 31, 2006

Source: Microwave News, July 31, 2006

This was only the beginning of Vijayalaxmi’s genotox opus. Many more papers would follow. She has published a total of 29 RF papers since 1997, with eleven in Radiation Research alone.5,6

Vijayalaxmi has had close ties to many of the other “no effect” authors in the slide, including Isabelle Lagroye, Joseph Roti Roti and Maria Scarfi —all of whom have received money from cell phone companies. Roti Roti, of Washington University in St. Louis, was commissioned by Motorola to cast doubt on the Lai-Singh work —which he did. Kheem Bisht and Robert Malyapa were members of his lab. (Roti Roti died in February.) She has also worked with James McNamee; his papers do not disclose sources of funding.

Lai-Singh have not been Vijayalaxmi’s only target. She has gone after just about anyone who has reported DNA breaks. In 2006, she teamed up with McNamee and Scarfi to criticize Hugo Rüdiger’s experiments at the University of Vienna. Rüdiger had followed up on the DNA work under the EC’s REFLEX program using human fibroblast cells, and he too reported breaks. Vijayalaxmi and crew called the work “questionable.”

More recently, in 2020, she took issue with the National Toxicology Program when it reported DNA breaks in the same type of cells that developed tumors following long-term exposure (more here). Here she warned of “serious weaknesses” and urged that the NTP report be interpreted “with great caution.”

Vijayalaxmi and Ken Foster Team Up

One of Vijayalaxmi’s coauthors on the NTP critique is Kenneth Foster, another RF veteran. He is also a coauthor of her new paper in the International Journal of Radiation Biology. Foster has been a professor of bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia for close to 50 years (he is now emeritus). Before that, he did microwave research for the U.S. Navy.

Vijayalaxmi and Foster’s new paper is the third in a series, all with the same theme: the sorry state of RF research, in particular genotox research.7 You only need to read the titles of the papers to get the message: Don’t trust reports of DNA breaks, even those with statistically significant results.

The title of the first, published in the summer of 2021, was “Needed: More Reliable Bioeffects Studies…” A few months later, they followed up with “Improving the Quality of RF Research…” And, now, the latest: “The Need for Consensus Guidelines to Address the Mixed Legacy of Genetic Damage Assessments for RF Fields.”

Vijayalaxmi and Foster offer a way forward: Start from scratch. “The positive studies,” they wrote “should be redone with tighter quality control to establish the reliability of the findings.” (No word about redoing the negative studies.) The subtext is clear. The studies showing effects won’t stand up to scrutiny.

Along the way, they rarely miss a chance to take a swipe at Lai-Singh. In their latest paper, they include an evaluation of a small subset of the genotox literature: just 29 papers out of the hundreds. Mirabile dictu, two by Lai-Singh and one by Rüdiger made the cut. All three were found wanting.8

Applying a Double Standard

Vijayalaxmi and Foster have far laxer standards for studies that don’t find effects. In one prescription for better RF science, they lavish praise on a million-dollar German study, which had been sponsored by the Federal Office of Radiation Protection (BfS) in 2005 in response to Rüdiger’s DNA breaks. The study, led by Petra Waldmann, found “no evidence of a genotoxic effect” in RF–exposed human lymphocytes. It is “meticulously controlled” and “impressively well-designed,” Vijayalaxmi and Foster gushed; Waldmann had produced “high-quality evidence.”

The reality is very different. The BfS/Waldmann project was a mess from beginning to end. It went on for close to a decade and produced very little of any value. Part of the problem was that Waldmann had limited experience running a research project —she was out of her depth.

At the outset, the BfS had been warned not to use lymphocytes because, as Rüdiger had already shown, they don’t respond to RF. But that’s what Waldmann did. It would take her seven years to publish the results. By then, 2013, the Rüdiger affair had faded away, if only because of constant bludgeoning by Alexander Lerchl, another BfS favorite, whose campaign to discredit the Rüdiger work was not unlike Vijayalaxmi’s against Lai-Singh.9

In response to complaints about the use of lymphocytes, the BfS gave Waldmann (and Paul Layer, a far more senior researcher) a second contract, valued at $700,000, this time to expose fibroblasts, the cell type Rüdiger had used. These experiments were beset with even greater problems and, like the first effort, ran very late. The results were never published in a peer reviewed journal, or anywhere at all in English. The only report —in German— appeared eight years after the first Rüdiger DNA breaks paper.10

What’s “Minor” Support?

At the end of their new paper, Vijayalaxmi and Foster declare that they have “no potential conflicts of interest” that might color their outlooks. But their CoI11 included one qualification:

“In the past, K. R. Foster has received minor levels of research funding from Mobile & Wireless Forum, an industry group.”

The MWF is a research and lobbying group founded by Motorola in 1998.12 Today its members include Apple, Cisco, Intel, LG and Samsung.

In fact, Foster has received almost continuous support from the MWF for a very long time. He gets star billing in MWF’s 20-year anniversary report, which includes references to many of his published papers.

How much is “minor support”? I asked him. “My definition,” he replied, “is whether I could have earned more money flipping burgers for the amount of time I spent on those projects.”

That’s all Foster would say other than that he got less than he does from Social Security and his university pension. Then he closed the door. “No more questions please,” Foster wrote.

Lessons Learned

So, where are we now, so many years later? I asked Lai. Here’s his reply:

“We’ve come a long way in understanding how low-frequency and high-frequency EMFs can damage DNA and affect gene expression. There should no longer be much doubt that both are biologically active. I suspect that the principal mechanism of action relates to changes in reactive oxidative species. This can lead to both adverse and beneficial effects —at very low intensities.”

And then he told me:

“But the biggest change, at least for me, is that time has opened my eyes. I now see how the world really works: All too often, money and power dominate science.”

James Lin Weighs In

November 17, 2023

In his long-running health column in the IEEE’s Microwave Magazine, James Lin states that the Jody Cantu paper in Bioelectromagnetics is an indicator of a “paradigm shift” in the way the U.S. military looks beyond simple heating effects of RF and microwave radiation. (His opinion piece is open access.)

_________________________

1. In one of our exchanges, I asked Lai whether one can learn anything about biological activity by comparing counts of studies showing effects with those that don’t. Here’s what he said:

“Yes, one needs to look at the studies individually to judge their ‘significance.’ This is not a simple or easy task. There are no set formulas and reliable criteria at the present time for EMF research. Counting the number of ‘effect’ vs ‘no effect’ papers at least offers a glimpse of the state of the research. We cannot deny that the authors of the papers reported significant effects —at least statistically— in each study and the papers were peer-reviewed. In addition, I completely disagree with ‘replication.’ Science does not advance by replication, but by demonstration of consistency among data. Data that are inconsistent are generally eliminated eventually.”

2. Henry Lai also tracks papers on genetic effects of static and ELF EMFs (power frequencies). His May 23, 2023 update of that database with 330 entries is available here: 277 (84 percent) show effects. Of these, 171 address gene expression, with 163 (95 percent) showing effects.

3. The abstract of the paper states that the SARs were less than 0.01 W/Kg. But, as Lai pointed out, the dosimetry section (Table 2) indicates that the cells at the bottom of the culture dishes had SARs that were more than six times lower: 0.00155 W/Kg.

4. Examples of low SAR studies are in a paper Lai wrote with Blake Levitt last year.

5. Vijayalaxmi is a member of the physicists-say-no-DNA-breaks school. In 2009, she told the media in her native India:

“The results from several of my acute and chronic exposure studies have revealed that RF radiation emitted by mobile phones does not have sufficient energy to cause ‘breakage’ in genetic material.”

6. A list of Vijayalaxmi’s 29 papers, compiled by Lai, is here.

7. See the Appendix of their April 2023 paper.

8. More about the Waldmann and Layer projects for the BfS here.

9. Both Vijayalaxmi and Lerchl are advisors to the Japanese/Korean partial replication of the NTP RF–animal study.

10. Vijayalaxmi and Foster don’t mention gene expression in their new paper, though they do allow for genetic damage via oxidative stress. They wrote:

“RF fields are non-ionizing, in that the photon energy is insufficient to ionize molecules and create free radicals: the latter are well-known mechanism to induce biological damage from exposure to ionizing radiation such as X-rays and gamma rays. Consequently, the energy from RF at levels below those sufficient to induce thermal damage would not be expected to induce genetic damage directly. However, some authors have suggested indirect mechanisms for genetic damage, for example due to oxidative stress resulting from RF-EMF exposure. In view of potential health consequences, careful studies on possible genotoxic effects of RF-EMF exposure are called for.”

11. Foster and Vijayalaxmi’s CoI statement in one of their 2021 papers is more ambiguous:

“Conflict of Interest: KF has received minor support for research on an unrelated topic (thermal dosimetry) by Microwave and Wireless Forum, an industry group. The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.”

12. The MWF was originally known as the Mobile Manufacturers Forum (MMF).