News Media Nix NTP Cancer Study

“Don’t Believe the Hype”

Are More People Getting Brain Tumors?

GBMs, the Most Virulent Type, Are Rising

Senior managers at the National Toxicology Program (NTP) released the preliminary results of their cell phone radiation study late last week. They were so concerned about the elevated rates of two types of cancer among exposed rats that they felt an immediate public alert was warranted. They considered it unwise to wait for the results to wend their way into a journal sometime next year. Not surprisingly, the NTP report generated worldwide media attention.

There were some startling reactions. Both the American Cancer Society (ACS) and Consumer Reports immediately shelved their long-held, wait-and-see positions. In a statement issued soon after the NTP’s press conference, Otis Brawley, ACS’ chief medical officer, said the NTP results mark a “paradigm shift in our understanding of radiation and cancer risk.” He called the NTP report “good science.”

Consumer Reports said that the new study was “groundbreaking” and encouraged people to take simple precautions to limit their exposures.

However, much of the mainstream media saw it very differently. This was apparent at last Friday’s news briefing where the skepticism among reporters was palpable. The Washington Post ran its story under the headline, “Do Cell Phones Cause Cancer? Don’t Believe the Hype.”

One question on many people’s minds was why, if cell phones cause cancer, there hasn’t been an uptick in the incidence of brain tumors in the American population. For instance, Gina Kolata, a science reporter at the New York Times, gave the NTP study zero credibility. In a short video accompanying the Times’ news story, Kolata said that there is “overwhelming evidence” that cell phones do not lead to cancer. “Despite the explosion of cell phone use,” she said, “it looks like the incidence of brain cancer has remained pretty much rock steady since 1992.” The “bottom line,” she concluded, is that, “You can use a cell phone without worrying.”

There’s More Than One Type of Brain Tumor

The issue of whether brain tumor rates are static or rising is more complicated than Kolata would have us believe. It’s true that the overall incidence of brain tumors has not been changing much, but a different picture emerges if one looks, carefully, at the data.

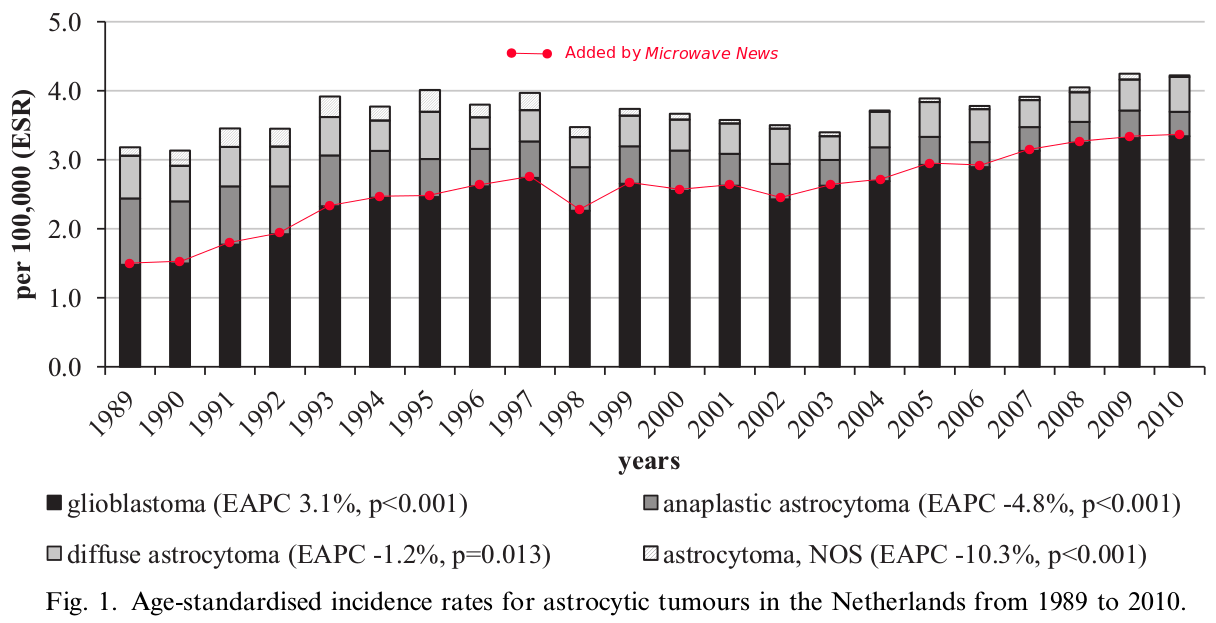

The histogram below helps tell the story. It’s based on brain tumor data from The Netherlands. The black segment of each column tracks the incidence of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the most aggressive and deadly type of brain tumors. While the total incidence of all types of brain tumors in The Netherlands rose at the rate of only about 0.7% per year, the increase in GBM was about 3.1% per year —that is, the incidence more than doubled over the period 1989-2010. (Follow the thin red line we superimposed on the histogram to track the trend.) This is a statistically significant increase. At the same time, the rate of all the other types of brain tumors went down; these changes are also significant. The higher incidence of GBMs is being masked by the lower rates of the other types of brain cancer.

EAPC stands for estimated annual percentage change

Source: Adapted from Ho et al, European Journal of Cancer, 2014, p.231

GBMs Are Also Rising in the U.S.

A similar trend is occurring in the U.S., according to a team from the University of Southern California Medical School in Los Angeles. The USC researchers looked at the incidence of brain tumors in three “major cancer registries” over a 15-year period (1992-2006). In a paper published in 2012, they reported that GBMs had gone up while the other types had gone down. The study showed “decreased rates of primary brain tumors in all sites with the notable exception of increased incidence of GBM in the frontal lobes, temporal lobes and cerebellum.”

The increase in GBMs in the temporal lobe (the region of the brain closest to the ear and potentially to a phone) was seen in all three registries, ranging from approximately 1.3% to 2.3% per year, a finding that is statistically significant.

Some anecdotal evidence from Denmark also supports a rising incidence of GBMs. Back in 2012, the Danish Cancer Society reported a spike in GBMs. The Society quoted a neuro-oncologist at Copenhagen University Hospital as saying this was a “frightening development.” There wasn’t much of a follow-up other than the Society’s removal of the news advisory from its website. (See our “Something Rotten in Denmark.”)

Cell Phones Linked to GBMs

Perhaps, the increasing rate of GBMs seen in the U.S., The Netherlands and Denmark is due to some unknown factor. But, whatever may be going on, GBMs are on the rise.

While most cell phone epidemiological studies do not break out the risks for different types of brain tumors, Lennart Hardell of Örebro University Hospital in Sweden has done so. “We have consistently found an increased risk for high-grade glioma, including the most malignant type, glioblastoma multiforme grade IV [GBM], and use of wireless phones,” he told Medscape earlier this month. Hardell’s epidemiological studies were instrumental in IARC’s decision to classify RF radiation as a possible carcinogen.

In an e-mail exchange with Microwave News, Hardell confirmed the Medscape quote. He added that he has also found that, in an analysis of 1,678, patients with GBMs in Sweden, those who used wireless phones had shorter survival times.

How Big Were the Increases in Tumors in the NTP Study?

Another media skeptic, Seth Borenstein, a reporter at the Associated Press, posted a video in which he called the increase in cancer in the rats “very slight” and therefore the cancer risk “very small.”

This is in line with the report the NTP posted online last week in which it called the incidence of tumors “low.” But some observers think the cancer rates among the rats are in fact higher than the NTP is saying.

At the press conference, Joel Moskowitz of the University of California, Berkeley, School of Public Health pointed out that a number of the exposed animals, but none of the control rats, developed abnormally high cell growth rates —hyperplasia— in the same type of glial and Schwann cells where tumors developed in other animals. (An audio recording of the press briefing is available here.)

Moskowitz calls the hyperplasia cells “precancerous,” as does John Bucher, the associate director of the NTP, who released the study on Friday. It is commonly believed that hyperplasias will likely later turn into malignant tumors. Moskowitz estimates that while the NTP found tumors in 5.5% of the exposed male rats at the end of the experiment, when those with hyperplasia are included, the rate goes up to 8.5%. “That’s a remarkable finding,” he told Microwave News.

“I totally agree with Joel,” commented Ron Melnick, who led the team that designed the NTP study. “He has a valid argument.” Melnick also pointed out that, “The study had low power and was more likely to show no effect. The fact that it did makes the results more compelling.”

If the exposures had continued for longer than two years, the results may have been clearer. During the study planning phase, Melnick argued for running the experiment for at least another couple of months. If he had prevailed, the status of the hyperplasias would have been clearer. He was overruled.

“It might be that extending the observation until the rats die, tumors could arise from some of the observed hyperplasias,” said Fiorella Belpoggi of the Ramazzini Institute in Bologna, Italy, where she is the director of research and the head of pathology. “But,” she added, “the NTP results are indeed sufficient for considering cell phone radiofrequency radiation as carcinogens.”

Belpoggi and her colleague Morando Soffritti recently released their own large animal study which showed that another type of non-ionizing radiation, ELF EMFs, can promote cancer. They are also in the midst of their own large RF animal study, but it has been delayed by a shortage of funds.

Even if the naysayers are right, Melnick maintains that a small risk could result in a large number of people developing radiation-induced tumors. That’s because there is a huge number of cell phone users across the world.

In the end, we checked in with Jonathan Samet of the USC School of Medicine for his opinion. Samet is a member of NCI’s National Cancer Advisory Board. In 2011, he chaired the IARC panel that designated RF radiation as a possible human carcinogen. Here’s part of what he told us via e-mail:

“From my perspective, the new findings, like the epidemiological findings considered by IARC, provide an indication of potential risk that needs careful follow-up. Perhaps these findings, along with prior epidemiological research, will motivate a comprehensive research initiative.”