RF Cancer Promotion:

Animal Study Makes Waves

Germany’s Alex Lerchl Does a U-Turn

The RF–cancer story took a remarkable turn a few days ago. A new animal study challenged many of the assumptions which lie at the heart of claims that RF radiation —whether from cell phones, cell towers or Wi-Fi— are safe.

The new study, from Germany, a replication of an earlier experiment, also from Germany, found that weak cell phone signals can promote the growth of tumors in mice. It used radiation levels that do not cause heating and are well below current safety standards. Complicating matters even further, lower doses were often found to be more effective tumor promoters than higher levels; in effect, turning the conventional concept of a linear dose-response on its head.

And for those with the stamina to have stayed tuned to the slow-moving RF–health soap opera, the new paper offers an unexpected surprise. The lead author of the new animal study is Alex Lerchl, who for years has charged that the only science showing low-level RF effects is bad science. Now the one whom activists had accused of being an industry lackey is being hailed as a hero.

Lerchl has shown that mice exposed in the womb with a known cancer agent, ENU, and then exposed to a UMTS cell phone signal had significantly higher rates of tumors of the liver and the lung, as well as of lymphoma than with ENU alone. (UMTS is a third generation, 3G, system based on GSM.) His study was designed to repeat, with a larger number of animals, an experiment published in 2010 by Thomas Tillmann of the Fraunhofer Institute of Toxicology and Experimental Medicine in Hannover. When Tillmann first presented his results a couple of years earlier, he called them “remarkable” (see “3G Can Promote Tumors”). Since then, the study has been largely ignored —until now.

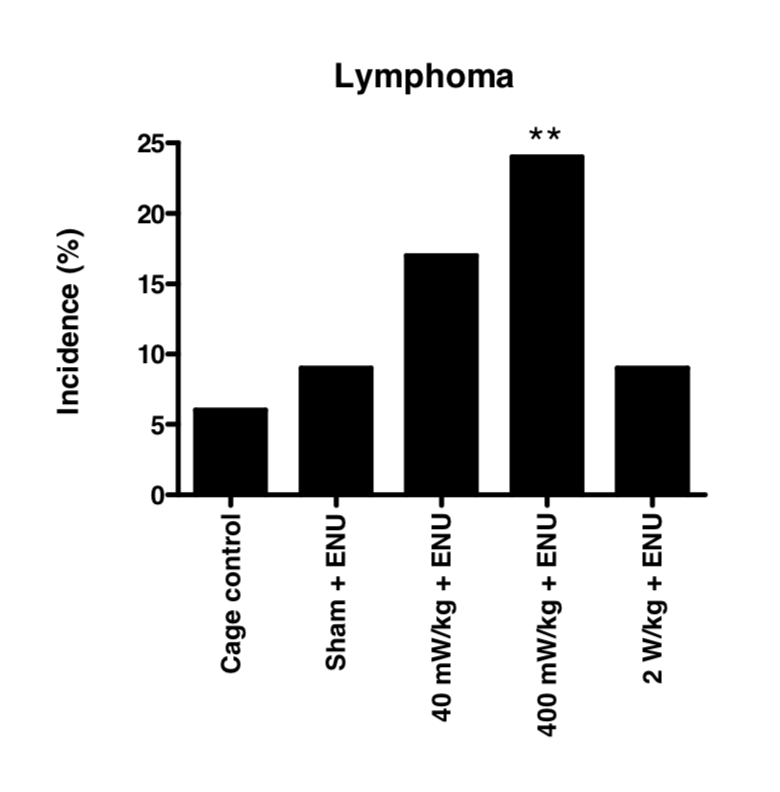

Lerchl found higher rates of cancer among mice exposed to SARs of 0.04 W/Kg, 0.4 W/Kg and 2 W/Kg —and in some cases, the lower the dose, the more cancer. For instance, he saw a higher incidence of lymphoma at the two lower doses than at 2 W/Kg, as shown in the histogram taken from his paper, which has been accepted for publication in Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications:

From Lerchl’s BBRC paper, Figure 1; “**” indicates that the result is significant at p<0.01.

“Our results show that electromagnetic fields obviously enhance the growth of tumors,” says Lerchl in a press release issued by Jacobs University in Bremen, where he is a professor of biology. He declined to respond to requests for comment from Microwave News.

Lerchl’s animal study has one advantage over many of the others that have been carried out in the past: He, like Tillmann, used free-roaming animals. In a misguided effort beginning in the 1990's, the EC supported a series of animal studies, known as PERFORM-A, at a cost of over $10 million, in which the animals were restrained to better quantify exposures. The entire enterprise turned out to be a fiasco. The exposure system was found to put the animals under sufficient stress to obscure the possible effects of the RF exposure (see our report: “Wheel on Trial.”)

The new study was sponsored by the German Federal Office for Radiation Protection (BfS).

The New Lerchl vs. the Old Lerchl

Lerchl’s findings have prompted a sharp change in his outlook. Some years ago, he was almost ready to declare that RF is cancer-safe. Most studies with cells and animals showing damage due to RF “could not confirmed,” he wrote in a 2007 opinion piece published by FGF, the now defunct RF research group run by the German telecom industry. It seems that, he went on, “non-thermal HF EMF have no adverse health effects.” Lerchl did leave the door slightly ajar, stating that more research was needed.

In the years that followed, Lerchl was a relentless critic of what he claimed to be shoddy science that pointed to EMF effects. In one case, the REFLEX project, he charged that RF-induced DNA breaks were only found because the experiments were rigged (see our “Three Cases of Alleged Scientific Misconduct.”) Lerchl also made it a habit of writing critical letters to the editors of journal that published papers showing EMF effects, sometimes forcing them to be retracted (see: “Lerchl Bags Another Trophy.”)

Some of Lerchl’s old adversaries see this new paper as a turning point. Franz Adlkofer, the former head of the REFLEX project, issued a statement calling Lerchl the “longstanding chief witness for the harmlessness of mobile communication radiation” and his new study as the worst possible outcome for the telecom industry. Adlkofer is now chairman of the board of the Pandora Foundation, a group that helps support research that is opposed by industry, with a special focus on RF radiation.

Enough To Change RF to a “Probable” from “Possible” Cancer Agent?

Current RF standards are based on the assumption that exposures below 4 W/Kg are safe and the radiation does not entail a cancer risk. “The fact that both studies found the same tumor-promoting effects at levels below the accepted exposure limits for humans is worrying,” write Lerchl and his colleagues.

Beyond the safety standards is the equally controversial issue of cancer. In 2011, a panel convened by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified RF as a possible human carcinogen. At the time, the panel stated that there was only “limited evidence” of cancer promotion from animal studies. The confirmation of the Tillmann study by Lerchl could change that. (The panel had little to say about the Tillmann paper; see p.279 of the IARC RF Monograph.)

“This new study, in conjunction with previous work, makes a much stronger case for an IARC classification of 2A, a probable human carcinogen,” said David Carpenter, the director of the Institute for Health and the Environment in Albany, NY, in an interview.

Lung Cancer Linked to Pulsed EMFs in 1994

While most RF–cancer studies have looked at brain tumors, as well as acoustic neuroma, there is a precedent for a link to lung cancer seen by Lerchl. In 1994, a major French and Canadian epidemiological study found a “strong” association between pulsed EMF signals and lung cancer among electric utility workers. The nature of that link could not be sorted out because the sponsor, Hydro-Québec, blocked further access to the data set (see our report: MWN, N/D94, p.1 and p.4).

We asked Paul Héroux, who designed the EMF meter for the French-Canadian study, about the Lerchl paper. “There are some obvious parallels between the new German study and what we showed 20 years ago,” he told us, “both show exposure to pulsed electromagnetic energy, both show EMFs to be a cancer promoter and both show a link to lung cancer.”